Your Product is a Pot of Jollof

Why Your Engineers Care

I'm out. I'm done. I can't be part of it anymore."

That’s what my friend, a brilliant product manager, told me over drinks a while back. He wasn’t just tired; he was furious. He’d just quit a job he was once passionate about, and the story came tumbling out of him.

"We were building a monster, man," he said, leaning forward. "A soulless feature factory, and I couldn't stand by and watch the train go off the cliff."

It had all started so well, with the team on the ground, talking to real people and solving real problems. But then the call came down from above. The mandate shifted overnight. Discovery was dead. The new mission? Write a massive, sprawling, end-to-end requirements document for a product that didn't even exist yet.

He threw his hands up in the air. "We were guessing! Guessing at problems our customers might have years from now. I remember yelling in a meeting, 'This 'MVP' is already version 5.20.3!'"

He knew exactly where that train was heading: a burned-out, cynical team, a bloated and confusing product, and a sea of disappointed customers. His team was so obsessed with the flashy what that they were completely ignoring the foundational how.

His story hit me hard because it’s a truth that sits at the very core of the disconnect in our industry. It’s the chasm between product managers and their engineering counterparts. We see a list of features. They see a system. And until you learn to see the system, too, you’ll always be speaking a different language.

Forget Software. Let’s Cook.

To understand what your engineers see, let's forget about code and think about something more fundamental: making a perfect pot of Jollof rice.

If you’ve never had it, Jollof is a beloved West African one-pot meal. Making it isn't a single action; it's a system at play.

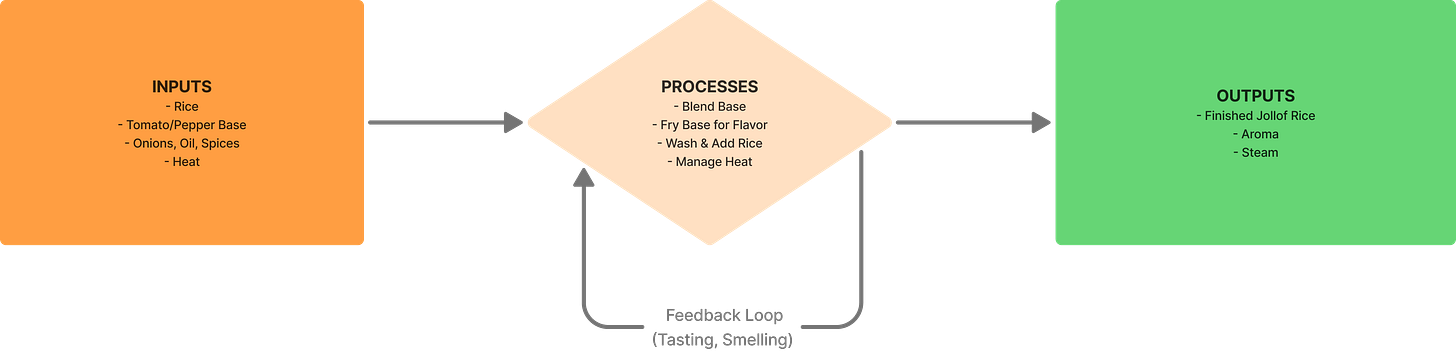

Inputs: You gather your raw materials rice, fresh tomatoes and peppers for the base, onions, oil, spices, and heat from the stove.

Processes: You execute a series of steps. You blend the base, fry it to develop its flavor, wash the rice, add it to the pot, and manage the heat to cook it through without it getting mushy.

Outputs: You get your finished pot of Jollof rice. But you also get other outputs, like the incredible aroma that fills the kitchen and the steam rising from the pot.

This is a system full of dependencies and feedback loops. You can't cook the rice without water (a dependency). A great cook doesn't just follow a recipe blindly; they use feedback to guide the process. They taste the stew base for seasoning before adding the rice. They check the texture of the rice to see if it needs more water. The smell is another feedback loop it tells you if the rice is cooking well or starting to burn.

If the rice comes out mushy, you don't blame the rice. You think like a systems operator. Was there too much water (input)? Was the heat too high for too long (process)?

You understand that changing one part of the system affects the entire output.

From Jollof Rice to Your Product

Your digital product is no different. It’s a system of inputs, processes, and outputs.

Inputs: User clicks, data from an API, keyboard entries, a webhook from another service.

Processes: The "black box" of the backend. This is the business logic, the algorithms, and the data transformations that turn inputs into something useful.

Outputs: A new screen loading in the UI, an email sent to a user, a record saved in the database, a response sent back to an API.

This is why the "simple feature" you requested can sometimes get a hesitant look from your tech lead. You're seeing the output ("we need a button that exports a CSV"). They are seeing the entire system.

They’re thinking: Where does the data for the CSV come from (input)? What process needs to run to gather and format it? Is that process so intensive it could slow down the whole system for other users? What are the dependencies?

When your engineers seem to be overcomplicating a "simple" request, they're often just doing their job: thinking about the system. They’re making sure the Jollof doesn't burn.

How Does This Impact Product Management?

So, how does seeing your product as a system actually change your day-to-day job? It’s a fundamental shift. You stop being a feature manager and start becoming a true product leader.

Your prioritization changes. Instead of just asking, "What feature has the highest business value?" you start asking, "What part of our system, if improved, would unlock the most future value?" You might find yourself championing a technical debt sprint not as a chore, but as a strategic investment in the health of your product.

You become a translator. You can now explain to stakeholders why a "simple" request has deep, system wide implications. You can articulate trade-offs with more confidence, building a bridge of understanding between the business goals and the technical reality.

Your partnership with engineering deepens. You’re no longer just handing off requirements; you're co-creating solutions. You start asking questions like, "How can we evolve the system to achieve this customer outcome?" This is how you earn their trust and become the strategic partner your tech lead has always wanted.

This isn't just about sounding smarter in meetings. It's about making better decisions, building more resilient products, and transforming your relationship with the people who build them.